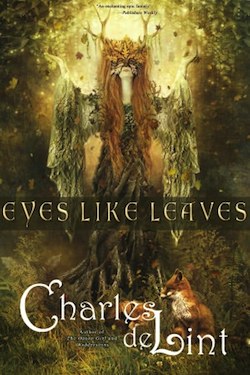

We hope you’ll enjoy this excerpt from Charles de Lint’s Eyes Like Leaves (which recently came out in paperback!):

Taking a delightful departure from his more common urban-fantasy settings, this epic tale from acclaimed author Charles de Lint weaves elements of Celtic and Nordic mythology while bringing sword and sorcery to the forefront. Summer magic is waning in the Green Isles, and the evil Icelord is encasing the lands in a permanent frost while coastal towns are pillaged by snake ships. Mounting one last defense against the onslaught, a mysterious old wizard instructs his inexperienced apprentice in the art of shape-changing. Mercilessly pursued by the Icelord’s army, this newfound mage gathers allies—a seemingly ordinary young woman and her protective adoptive family—and they flee north in a desperate race to awaken the Summerlord. Time is running short for the Summerborn, especially when a treacherous family betrayal is discovered.

First

Tarn knew him for a wizard, the tall greybeard, calm as a tree, with the wisdom of longyears patterning his sky-blue eyes. They met on the streets of Tallifold, a large port on the south coast of Fairnland, dhruide and streetsinger, Puretongue and Tarn.

“I have been searching for you,” Puretongue said. He touched the mark on Tarn’s brow that was shaped like a crescent moon. “I need a prentice. I have a task that reaches beyond my lifetime—in you I will see it fulfilled.”

Tarn’s eyes widened. A tremor of strangeness stole over him, fear mingled with bright wonder.

“Me?” he asked.

“You.”

“But, why?”

“The reasons are unimportant. Are you willing to learn what I can teach you? It won’t be an easy task.”

“I’ll try, but…” Tarn met the greybeard’s clear-eyed gaze. “Are you sure you haven’t mistaken me for someone else?”

“I am sure.”

“When will we begin?”

The tree-wizard smiled. “We have already begun.”

They left Tallifold that day, journeying north to where autumn touched the summer woods of Avalarn. The wind teased their cloaks with curious fingers. The sky dreamed blue above them. The woods whispered wise about them.

Listening, watching, Tarn began his lessons.

There was always salt in the air around Codswill, a small town on Cermyn’s east coast, even miles inland when the wind was right. Salt and the sharp odours of fish and fish-smoking, the smell of nets drying, for Codswill lived by its fishing trade. Its small boats timed their comings and goings to the tides. They spun and wove a spider’s web of nets across the waters of the Channel Sea by day, docking at the wharves by night like moths clustered about a flame.

Tarn Galdmeir stood at the window of his room in The Hart’s Inn, his hands on its broad sill as he stared out across the darkened town to the wharves. Beyond the small forest of ships’ masts, the restless waters of the Channel Sea shimmered with phosphorus and moonlight. It was almost midnight, in the late spring of the year 526, as reckoned by the Dathenan calendar.

Tarn was exhausted, but sleep eluded him tonight. Snatches of memories flitted like fireflies through the greyness of his fatigue. He listened to the sea murmur against the wooden pilings of the wharves, distant, but clearly audible in the quiet that wrapped the town. Closer, the inn creaked to itself in the darkness.

It was in an inn such as this in Tallifold that he’d lived years ago. He’d been just one more street urchin, eking out a meager living from singing in the streets, sweeping the inn’s main room for his board, pick-pocketing at times. But that had been before he met Puretongue.

“I can’t do it,” Tarn said.

“ You can.”

Puretongue’s voice was firm. His form shimmered in the firelight, grey hair and cloak feathering, shifting, changing…

The raven cawed once, a harsh, impatient sound, then the dhruide faced Tarn once more. His lips curved in a slight smile, eyes a-glint in the fire’s glow.

Tarn sighed and gathered his thoughts, focusing them as he’d been taught.

Forms are fluid when named, he remembered, so he named it: raven. He drew strength from the hidden places inside, from the dhruide’s lessons, from his own deep dreaming. He sought his taw—the inner silence where the power lay hidden. He saw his fingers shimmer, feather. His head ached as he reached for the shape.

Almost he felt the change…so close…

Then it was gone.

Lost.

“I’ll never learn,” he muttered.

“ You will,” Puretongue said softly. “ You must.”

It was a sense of discordance out there in the night that kept Tarn at the window. It was not so much the Saramand, though their Viking raids were worse than ever this spring. There was something else abroad in the night, something old and dark. An evil that he couldn’t name, and nameless it was a greater threat. He didn’t dare wake a seeking-magic to find it for fear that the spell would draw whatever it was to him, as surely as he was already drawn to it. He wasn’t about to repeat the wizard Jaal Osser’s mistake—seeking a hill mage, but waking instead the dragon-shaper that destroyed him.

He ran his fingers through his dark corkscrew hair and frowned.

Tarn looked up. High amidst the interweave of the oak’s branches he saw a snug house with a leafed roof and trailing vines that grew from the flower boxes under the windows. He smiled, thinking, where else would a treewizard live?

“How do we get up there?” he asked.

He looked for a ladder or a rope. The closest branch was twenty feet from the ground.

“I will have no difficulty,” Puretongue said. “But you will have to learn to feather yourself. It’s that, or sleep on the ground.”

He shapechanged. A raven lifted sloe-black wings, rose to disappear into the house. Tarn sighed and sat down, back against the oak’s broad trunk. When the evening deepened into midnight, he stood and called a question up to the silent house.

“How long do you plan to leave me down here?”

There was no answer except for the wind moving through the leaves high above.

Tarn kicked the tree. Cursing the sudden pain in his toe, he sat down again, damning all wizards and their incomprehensible methods of teaching.

The tea in the small clay cup on his nightstand was cold when Tarn finally turned to taste it. He returned to the window, sipping, and studied the night. His eyes were round and wide, a strange mingling of gold, grey and mauve. They pierced the darkness with the intensity of a wolf stalking its prey. His gaze roved the streets, searching for something more than the inky spill of long shadows. The buildings were black bulks with light spilling here and there from an unshuttered window. Then, at the end of a cobbled street, he saw movement, furtive and sly.

“I’m trying,” Tarn protested. “I really am. But everything you teach me just slips away when I finally think I understand it.”

“If you want to learn the old magics,” Puretongue said, “you must first put away your need to view it as a constant. Stop scribbling every little truth I give you in your notebook. How long is truth true for? The old knowledge is like a bird in winding flight—always in motion, ever changing.”

Tarn nodded. He heard in the dhruide’s words an echo of something he’d always sensed and had a sudden need to write the words down so that he would remember them. Writing was one thing that had set him apart from the other street urchins and he’d cherished that difference. But writing it down only perpetuated his present problem. He sighed and pushed the need from him—out of his mind, but not forgotten.

“There must be more to it than that,” he said. “I know there must be more.”

“More?” Puretongue chuckled. “Tarn, O lad. There are worlds within worlds more.”

Tarn looked away. As he lifted his gaze to the night skies, the darkness fell back before his eyes, growing ever deeper. The longer he looked, the smaller he felt. The stars loomed huge and brilliant while he diminished. The dark between them was an empty void without end. He shook his head in fearful wonder. He’d been with the tree-wizard for three weeks. Had he learned anything?

“How do I find it?” he asked in a small voice.

“Within yourself. The answers—”

“Lie within myself. I know. But knowing that doesn’t help. I’ve searched and searched till my head aches, but all I find are more riddles.”

The dhruide was silent. Then he smiled and laid his thin hand on Tarn’s brow, covering the moon-mark.

“There is power in names,” he said. “That is the Third Lesson of the Oak. So I will name you Galdmeir—Riddle-well. With the strength of that naming, you can’t fail.”

“But—”

“Don’t try so hard. Learn to be quiet inside. Still your inner conversations, your restless feelings. In your taw, in the heart of that stillness, you will find the answers to your questions.”

Tarn nodded. He tasted his new name, thought over what he’d been told.

“What of the First Men?” he asked, changing tack. “Those ancient people who set their mark across the hills. What can you tell me about them?”

Puretongue smiled, knowing where this new line of questioning was leading. “Know this: Those who lived here in the first days knew truth, and never hoarded it.”

“But what about their stoneworks? The longstones and towers, henges and roadways? They pattern the land, hinting at wisdoms, and they’re more lasting than any words my pen might put to paper, but they hide their secrets.”

Puretongue sat quietly, considering.

“ They are patterns,” he said after a moment. “Storehouses of…power some might say. And now I can see a use for your scribbling as well. Like the stoneworks, your letters can set echoes of those patterns reverberating in the minds of those who might read them.”

He regarded Tarn with a new interest, his deep blue gaze piercing through to the youth’s heart as though reading all he’d ever written, perhaps all he would ever write.

“And you have used your gift wisely,” he added, “I can see now, for all that you scarcely understood what you were writing down half the time. A wise man follows his deepest instincts—that is the First Lesson of the Birch.”

“Can you teach me to read the patterns in the stones?”

Puretongue smiled. “Do you have the time to walk the length and breadth of these Isles to read them? And then, when we are done, to start all over again, for they will have changed their tale before ever we reached the end.” He shook his head. “Listen to the voices of the stones if you must read them. Your taw can hear them speak, though you think you can’t.” He paused, then added, “These days they speak of things waking.”

“The old ways are returning?”

That was one thing Tarn never tired of hearing the dhruide tell—tales of the old days, before the coming of the Dathenan, when the Isles were ruled by wizards, and the Tus and erlkin dwelled in an uneasy balance.

“Something returns,” Puretongue said.

“Is it the Summerlord?” Tarn tried, remembering a certain tale.

Something flickered in Puretongue’s eyes and for a moment his shoulders seemed to bow under some great weight.

“The Summerlord’s kin,” he said.

His voice was like the wind hovering on the edge of a storm.

Tarn set the half-empty tea cup down on the windowsill and leaned forward. The moon-mark on his brow pulsed as he gathered his taw. That inner silence cloaked the jumble of his thoughts, clearing his mind. His range of sight deepened, his breathing slowed.

He saw two figures on the cobblestoned street, the first oblivious to the presence of the second. The first was mortal. The other, the stalker…

“A dyorn,” he murmured.

His blood chilled.

High on the downs above Avalarn, with his taw wrapped about him like a mantle, silence inside him like the soundless tread of the night, Tarn stood. His arms were outspread, his face serene, eyes closed. He looked inward. From that silence, he found the name he sought and took it. He shaped it with the power of his taw into a sound like wings the colour of his own dark hair and embraced the sky.

As he spoke the name his body shimmered, feathered. He rose into the air, sailed on the wind with a wild joy pounding in his heart. A dozen yards he winged, then faltered, tumbled down. The wide spread of a juniper broke his fall. He stood in the middle of it, bruised but triumphant, his face flushed with pride, then ran the remaining distance to Puretongue’s tree.

“I did it!” he cried, finding the dhruide gathering herbs in his garden. Not even the dull throb of a headache could diminish Tarn’s joy. “I did it!”

Puretongue looked up. That slow smile of his spread across his face, crinkling his moustache.

“I knew you would,” he said.

Tarn stilled the sudden leap of his pulse. He altered his normal vision into deepsight to pierce the night’s shadows and fixed his gaze on the dyorn. Time elongated into slow moments. He took in the misshapen body, powerfully muscled, the white hair that hung in greasy strands from its saurian-shaped skull. Its skin was swarthy, its leather tunic and trousers dirty. But the long length of its curved blade glittered bright and polished in a shaft of moonlight. It glittered menacingly, then disappeared as the dyorn moved into deeper shadows.

Tarn tracked it with his deepsight. With a rush of adrenalin, his first moment of fear shifted into excitement. He wasn’t a novice, helpless in the face of his first foe. He knew how to deal with Lothan’s stormkin.

He moved to the sill, balanced on the balls of his feet, poised and certain. Waiting a long moment, he loosed his taw. The power enfolded him, changing his flesh and shape. He was airborne, a winged form, swooping downward, the wind of his descent exhilarating as it rushed through his head feathers.

But by using magic, he had warned the dyorn.

Faster than he could have thought possible, the dyorn lifted his blade in a long sweep. Tarn dodged as the sword whistled by his wing, but he lost his balance in the process. His landing was ungainly, losing him precious seconds. Letting the winged shape fall from him, he rolled to his feet, shaping a scabbarded blade at his back. It was a twin to the dyorn’s weapon, a two-edged sword, slightly curved, with a guardless hilt. He ripped it from its scabbard, only just catching the dyorn’s second blow.

He felt the violence of the impact all along the length of his arm, dodged, then stepped in and to the side. Their blades engaged again in a quick flurry of movement that warned each of the other’s skill before they broke apart.

Tarn reached inside himself to shape his taw, but the dyorn charged, denying him the moment’s respite he needed to harness his magic. Cursing, he fell back before the creature’s onslaught. He could hardly defend himself, much less attack. He’d been too sure of himself, he realized—a lesson he might not live to profit by.

Centering his deepsight on the dyorn’s unblinking gaze, he continued to fall back, feigning a weakness in his defense. He let the dyorn almost catch him in a whirling figure-eight weave and took another step back, only to feel the stone wall of a building. The dyorn grinned.

Tarn sidled left, stepping into the dyorn’s next attack. They grappled for a moment, the creature’s foul breath heavy on Tarn’s cheek. Disengaging, he sidestepped, repeating the figure-eight weave, again feigning the weakness, before rolling under the creature’s long reach. He felt the sting of a cut along his upper arm as he came to his feet.

Their blades clashed again and he opened his defense a third time. He caught the glitter of anticipation in the dyorn’s eye and twisted his blade to meet the expected attack. In and around their swords wove their figure-eight, but Tarn dropped to his knees. His blade became a blur in the shadows as he swept it in, thrust up and forward. The dyorn toppled onto him, the hilt of his blade striking Tarn on the shoulder. Tarn heard the clatter of the sword as it fell to the cobblestones behind him and bowed under the sudden dead weight of his foe.

Rolling free, he pulled out his sword and stood. His breath laboured in heavy rasps and he slowed his pulse with an effort. He stared down at the slain dyorn, and he felt a little weak as the rush of adrenalin evaporated. His eyes misted and a throb began at the back of his head. The shapeshifting took its toll, brief though it had been, and coupled with the way he’d overused his powers these past days. He knelt beside the dyorn, cleaned his blade and sheathed it. But he was too weak to unshape it. It hung on his back like a leaden weight. His earlier weariness rushed up to meet the throb in his temples.

Three days ago the summoning had come to him in Tallifold. Expected as it had been, it still took him by surprise. He’d woken from a dream to hear the heavy footsteps of Saramand soldiers thumping on the stairs of the inn where he was staying and known he was discovered. He’d left through the window, a feathered shape winging through dawn’s early light, and headed north, as the dream had bid him to.

North…

Leaving Tallifold on swan-wings, watching the fields unfold below, finding the familiar skies above Hemenbrawe Wood, remembering the woods of Avalarn and the times gone…how many years?…hiding from the invader, awaiting the summons Puretongue had said would come…but the dhruide himself was gone…his own youth was gone…and the summons…

Had finally come.

Wings gave way to the sure-footed lope of a wolf’s gait, the swift graceful pace of a stag, shapes not lightly taken, but filling the heart with a lawless joy, drawing from the hoarded powers of his taw, replenished when he could…

A day as a drowsy oak, broad leaves taking strength from the sun, tangled roots nourished in the dark rich earth…nearing Codswill…by night now, the white horn gleaming on his brow, sharp hooves cutting the sod… north and north as the miles fell away behind…calm as the moon dreaming silver on high in its web of stars…north to Codswill, the unicorn…

Stepping onto the beach this morn, sleek shape falling from him, woods behind…waif-thin now and curls all tangled, hearing the wind in the trees like a tune of old when the longstones were young…and mixed in its measures…the wave-washing harmony of the Channel Sea…

Tarn shook his head and looked around. The dyorn’s prey had long since fled—if it had even known it was being hunted. But the dyorn’s body remained. If he weren’t so tired…

His swift journey north, the years of hiding, had worn him down more than he’d thought. Tempered him, perhaps. Made the magics more ready at hand. But it had done little to curb his impatience. He wanted to be doing, not waiting; and now that the time for action had come he moved too quickly, spent his energies when he should have been hoarding them as never before.

Oh, Puretongue, he thought. I’ve still to learn patience.

Bone-weary, he delved inside himself to find a shape for one more task. Finding it, he named it. His thin shoulders widened, his chest deepened. The ache in his head was a steady pounding as he stooped to lift the dyorn. Slowly he set off with his burden, leaving the town behind. There were enough rumours of stormkin abroad without adding fuel to them by leaving a corpse where anyone could trip over it. These creatures fed on the fear that such a rumour would generate.

He secreted the corpse in a thorn thicket, far from the town and the roads leading into it. As he pushed the last branch into place, his stomach gave a lurch. Too many shapes, held too long. He pitched forward. The shape he wore fell away like a discarded cloak and he lay as he’d fallen: a slender form, dark like a stain upon the grass.

He woke to find the sun hot on his back. Slowly he rolled over to stare up into a brilliant blue sky. For long moments he simply lay there, letting his mind clear. When he finally sat up, he rubbed the moon-mark on his brow and smiled, feeling rested for the first time in long days. The forced sleep had done much towards making him feel whole again. For awhile he’d been stretched too thin, his life essence elongated, as he drove himself on. But now—

He remembered the previous night in a rush.

The dyorn he’d slain—it had been hunting. What had become of its prey? He turned his thoughts back to that moment before he’d recognized the dyorn for what it was. His deepsight had shown him a young woman, plainly featured but with bright red hair. And there’d been something about her…

He shook his head, recalling again his summoning dream. He was to go north. And in Codswill, just before Beltane, he would find a mage that he must lead to Pelamas Henge. To the Oracle there. Beltane night was less than three days away now. That was the reason, as much as the Saramand pounding on his door, that he’d come north with such speed. But once he’d reached Codswill, he’d not found even the whispered memory of a mage.

Again he thought of the dyorn’s prey. Her? Was she the mage? The one he must lead to the Oracle at Pelamas? If she couldn’t even fend off a dyorn…

He stood up, still undecided, and returned to the town. He’d left his staff and pack in his room. Hunger rumbled in his belly. He could do with a meal. He would eat, then go ask in the market again today. And if he saw a girl with flame-red hair…well, she wouldn’t be too hard to miss in a town of dark-haired Dathenan. And if she were the one he sought…

“Aye, I remember her,” the old fisherman said. He set his half-mended net aside and took the time to relight his pipe before he went on. “Hard to forget hair that bright. Think she came with the latest landless out of Meirion—docked yestermorn. The ship’s long gone back for more.” He shook his head and spat on the dock. “Terrible business. They say the invader plans to strike at Cermyn next. What do you think?”

Tarn shrugged, hiding his impatience. It was still before noon and the day was warm. Gulls winged over the wharves, their cries like the sharp haggling of chapmen. Salt was strong in the air, the reek of fish stronger. Danger and talk of war seemed out-of-place.

It was a peaceful scene, Tarn conceded, for all the fisherman’s words. But the undercurrent could not be ignored. There were too many refugees, housed wherever there was room—and that was fast coming to a short supply. At one time or another throughout the morning, he’d noticed there were three or four of the landless staring east across the waters to where their lost homes lay. The spectre of war reared its head. And, Tarn thought, remembering his own mission, there was more than the Saramand to contend with. There were stormkin abroad— like last night’s stalker.

“The girl…?” he began.

But the fisherman cut him off. “Dath! If the king had any guts he’d have sent men into Fairnland and Gwendellan when the snakelovers first landed. Then we’d not be overrun with homeless crofters, nor fearing the threat our own selves.”

“Do you know where I can find her?”Tarn asked.

“Eh?”

“The girl. With the red hair.”

“Her?” The fisherman shrugged. “Left this morn, she did, with a pack of tinkers—least I think it was her I saw on my way down here after breakfast. Had the same hair, sure enough, though it hung down her back in a long braid today. Say.” He regarded Tarn curiously. “Why are you looking for her? Are you kin?”

Kin? Tarn remembered kin.

“The darkness will grow, Tarn,” the old wizard said, “before ever it diminishes.”

“But why?”

He was close to understanding much, but for every knowledge gained, a new chasm of ignorance opened under his feet.

Puretongue sighed. “Who can say? The weavers weave, Meynbos, the Summerlord’s staff, is broken—and with it, his power. Year by year his strength flows from him, like blood from a wound. That wound is almost dry now, Tarn. The summers will grow colder until they fail altogether. And then the Icelord alone will rule the Green Isles.”

He made the Sign of Horns as he spoke Lothan’s name.

“We do what we can,” he continued. “I, and a few others who still have our magics. But we grow thin. We bind the old evils to their prisons and seek to keep the Everwinter at bay. But this is a god’s work, and none of us are gods. The time will come—all too soon, I’m afraid—when we will no longer have the strength for our tasks.

“The Woodlords are forgotten and the erlkin no more than a memory. We need to return wizardry to the Isles, we need to wake the sleeping magic of the Summerlord’s kin. They wander through their lives, unaware of the Summerblood that sleeps inside them. But they hold the final fate of the Isles in trust, whether they know it or not. Woken, they will either aid Hafarl, or avenge his death.”

“What can I do?” Tarn asked.

“Magic is like a fever, Tarn. Each spell you use echoes across the Isles, waking in turn the sleeping taws of the Summerborn—Hafarl’s kin.”

Tarn met his gaze steadily. “I’m only one person, Master, and a small one at that. Your time might have been better spent opening a school of magic, instead of teaching one streetsinger spells.”

The tree-wizard shook his head. “Do you think it will stop with you? Your strengths are growing. Given time, your taw will be as deep and still as your name. The magics will spread from you. Each spell you use affects more than the task at hand—that is why such care is needed when you use magic. Echoes of each spell will ripple like long waves across the land and who knows how many they will wake?”

“And that’s all I have to do?”

Puretongue smiled sadly. “There will be another task. I have foreseen that much. But the summons to begin it will come from Hafarl—not from me.”

Tarn sat quietly, awaiting more. The dhruide looked away into unseen distances, his eyes bright and shining.

“What will the task be?” Tarn prompted at last.

“You will gather the Summerlord’s kin.”

The summons had come, but it hadn’t been clear. The dream had sent him north to find only one mage. Perhaps if the Saramand hadn’t come pounding up the stairs, the dream would have told him more.

“Kin?” he said, repeating the fisherman’s question. “No. But I think I know her.”

“Well, she’s travelling with tinkers now, lad. That’s all I know.”

“Where do you think they were bound?”

The fisherman scratched his chin. “Well, it’s late spring, isn’t it? Then I’d say north.” He pointed with his pipe. “Up into Umbria and Kellmidden for the summer fairs.”

He left Codswill by the north coast road, following the half-day-old trail of a tinker’s wagon. The more he considered the red-haired girl, the more certain he became that she was the one he sought. That she hadn’t used her powers against the dyorn, that he hadn’t even sensed power in her…those were riddles that would remain unanswered until he caught up with her.

Night came when he was miles from town, still walking. His staff made tiny holes in the dirt beside his footprints. He wrapped his cloak around himself to ward off the night’s chill. Gathering the endless questions that rose in his mind, he spun them into silence.

He longed to lift above the road in winged flight, or to feel the distance disappear under sharp hooves, but he contented himself with the more mundane mode of transportation that was his own two legs. He needed to conserve his strengths now for the tasks that lay ahead. And if there was one dyorn abroad, there might be more, or other of the Icelord’s creatures. Any use he might make of his magics would draw them to him as surely as the moon draws the tides.

There would be time enough for spells when he caught up with the girl. If she were the one he sought, she’d know more than him anyway. He could wait for her guidance. She knew enough to head north, didn’t she? And north lay Pelamas Henge and its Oracle.

Eyes Like Leaves © Charles de Lint 2009